It was a dark and stormy night...

“Always in the middle of the night and usually during a rainstorm…just part of the job,” mused the kindly old English veterinarian. He was just cleaning up after delivering the prize sow’s piglets when farmer Wallace, a border collie, and his young son Timmy arrived with more buckets of hot water. “How many?” queried the Yorkshire farmer. “Ten, plus a runt,” answered the vet. “What’s a runt?” asked the inquisitive young lad. “A piglet that may be too small or weak to survive. Let’s go back to the house for some tea by the fire, and I’ll tell you all about it!”

“Always in the middle of the night and usually during a rainstorm…just part of the job,” mused the kindly old English veterinarian. He was just cleaning up after delivering the prize sow’s piglets when farmer Wallace, a border collie, and his young son Timmy arrived with more buckets of hot water. “How many?” queried the Yorkshire farmer. “Ten, plus a runt,” answered the vet. “What’s a runt?” asked the inquisitive young lad. “A piglet that may be too small or weak to survive. Let’s go back to the house for some tea by the fire, and I’ll tell you all about it!”

Today’s Episode

There are several ways that networks can resemble barnyards, but we promise today’s informative post will be 100% manure-free—as long as we stay away from certain departments’ file servers!

One of the errors that can be sometimes seen on an Ethernet network is the occurrence of a “runt frame.” Like runt piglets, runt frames are smaller and not as healthy as they should be. Unlike piglets, (which can be rescued with special care), runt frames must be thrown away by properly working Ethernet equipment.

Healthy, Normal-Sized Ethernet Frames

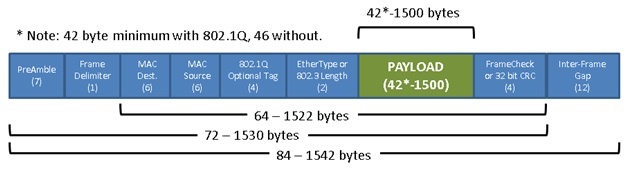

Before we talk about smaller-than-normal Ethernet Frames, it helps to review what a normal Ethernet frame looks like. As we see in the diagram below, an Ethernet frame must be AT LEAST 64 bytes long (excluding PreAmble, Frame Delimiter, and Inter-Frame Gap).

A Standard Ethernet Frame

When Smaller Isn’t Better

When a program only needs to send a couple of bytes of information in an Ethernet frame, it is forced to add ‘padding’ of extra ‘empty’ bytes/octets in order to make the Ethernet Frame large enough to be sent on the network. This is akin to using massive quantities of bubble-wrap for a small item being shipped in a large box. It may seem like wasted space, but the shipping company won’t ship boxes smaller than a certain size!

When a program only needs to send a couple of bytes of information in an Ethernet frame, it is forced to add ‘padding’ of extra ‘empty’ bytes/octets in order to make the Ethernet Frame large enough to be sent on the network. This is akin to using massive quantities of bubble-wrap for a small item being shipped in a large box. It may seem like wasted space, but the shipping company won’t ship boxes smaller than a certain size!

Why Have Minimum Frame Sizes?

So the most obvious question that technical people ask at this point is: “Why have a minimum Ethernet frame size?” This is an excellent question. To answer, we need to travel back in time to look at how the original Ethernet networks operated. If you were around in those exciting days of yesteryear, Ethernet was not cabled with telephone-like connectors—it was cabled with a single, thick cable that snaked through a computer room, with individual computers “tapped” into the same conductor, which was used for both sending and receiving frames.

In order to allow multiple computers to share a single wire for both transmitting and receiving, a number of rules needed to be set up. These rules were designed to keep transmissions safe from interference by other computers and to establish some rules about sharing the network cable fairly.

In order to allow multiple computers to share a single wire for both transmitting and receiving, a number of rules needed to be set up. These rules were designed to keep transmissions safe from interference by other computers and to establish some rules about sharing the network cable fairly.

When two computers attempted to send frames on the Ethernet cable at the same time, the two “conversations” would interfere with each other as the signals “collided” with each other on the cable instead of being delivered to the intended receiver. In order to avoid these collisions, engineers designed a set of rules known as “CSMA/CD: Carrier Sense Multiple Access, Collision Detection” which we’ll cover in detail in a later episode. For our discussion here, we just need to know that collisions happen when more than one computer transmits on a single line at the same time and the CSMA/CD rules help to avoid this.

One way to help avoid collisions is to have a minimum frame size. Longer frames make it easier for the other computers to tell when somebody else is using the network cable and helps them avoid talking at the same time. Think of the original Ethernet as one giant conference call on a speakerphone: If people always recite a full paragraph of text before leaving the line open for others there will be far fewer instances of two people talking at once than if each caller was only able to randomly shout only a single word, and then wait a random number of seconds. The longer chunks of information being sent are more noticeable and easier to avoid “talking over.”

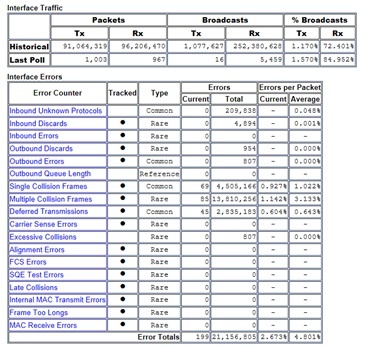

Manufacturers of networking equipment have deployed two major revisions of counters designed to track LAN interface errors. The original set of counters is known as RFC-1213 and a later more extensive set of counters was introduced with the RMON standard. When looking at the original standard (RFC-1213), many people are surprised to see that it does not include counters for “Runts.” Instead, runt packets typically show up in other measurements. Usually, runt packets will show up in the counters as a high number of collisions (Single Collision Frames and Multiple Collision Frames) as this is a prime cause of runt frames. You may also see high levels of Alignment Errors on your network, depending on how the runt packets are interpreted by network devices.

Interface Errors Display in PathSolutions

Despite the lack of a dedicated error-counter in the RFC-1213 standard, many types of network capture equipment, protocol analyzers, and troubleshooting equipment track and count runt frames on a network link. Unfortunately, these analyzers typically only diagnose one network link at a time so the network admin is still left with the problem of finding the offending network connection.

The RMON network monitoring standard introduced two new counters, (etherStatsUndersizePkts & etherStatsFragments), which were designed to track and count runt frames. In our lab and field testing, we’ve found some major setbacks to using these RMON counters to uncover runt packets.

The first setback is that many device manufacturers do not support RMON, or if they do, they support a very limited number of RMON groups. We’ve also found that even if a device supports a particular RMON group, they may not support the counters that you want and may not actually count and track runts since this requires support from the underlying network hardware and chipsets.

Another drawback to using RMON counters is that some manufacturers appear to be pulling away from RMON support since it can use a great deal of memory and CPU on their networking devices which may decrease their performance.

In the standards bodies, where engineers are working on managing 40 Gigabit Ethernet and other new technology, there have been some recent debates about possibly adding a better set of counters to the next generation of networking gear and tracking runts better. If and when the standards bodies do add any useful counters to the standard, PathSolutions will be furiously testing network manufacturers’ implementations of the new standards and seeing how they help diagnose network problems so that we can continue to make our software (and our customers) smarter!

What Causes Runts

There are a number of possible causes of runts, none which should occur on a normal, healthy network! The most likely causes are excessive collisions, which may distort Ethernet frames, causing only the first half of a frame to be seen before it is cut off by a collision. (Imagine a limousine crossing the train tracks and only the first part of the car makes it across before the train collides with it and knocks off the rear wheels and trunk).

Other, less common causes may include: LAN interfaces or transceivers that have been damaged and are breaking the rules, sending out malformed/shortened frames, taking completely normal frames and shortening them as they are repeated down another network segment, or falsely sensing collisions that aren’t there. We have seen network hardware drivers that don’t pad the packets correctly, ignore inter-packet gap timing, or don’t police packet length properly. Fortunately, malfunctioning LAN interface chips are rare; when they are going to fail, they typically stop transmitting altogether. I say fortunate, since it can take a huge amount of time and troubleshooting expertise to find a malfunctioning LAN interface chip, especially if the problem is intermittent. (Dead interfaces are easy to diagnose, crazy interfaces are hard, and only slightly crazy interfaces can be next to impossible to find!)

Tip: If you are seeing only ONE interface reporting high collisions and alignment errors remove that one machine from your network and test it separately. If you are seeing ALL of your network interfaces report an error EXCEPT one happy interface that reports no problems at all remove the only “happy” machine from your network and see if the rest of your network suddenly gets well.

Until Next Time!

So now you know what a runt frame is, its symptoms and causes, and you should have an idea of what to keep an eye on and how to fix runt problems. Heavily congested network bottlenecks may need more bandwidth (a faster connection). High collisions and alignment errors on a lightly used interface may indicate cabling issues. If runts appear to be coming from a specific LAN interface, it may be time to check the health of that interface card, swapping the hardware out in order to see if the issue goes away.

Here’s hoping that your network is healthy and free from these “small” problems!

Image Credit – Bubble Wrap wikipedia.org: Bubble_Wrap